Written by Victoria Jefferies, current MA Early Years Education student.

Perhaps it was my unconventional beginning to a career in Early Years, or perhaps it’s my questioning and curious nature, but pursuing a MA has opened my eyes to the contested space we navigate. Educators are acutely aware of many of the difficulties we face: funding, staffing, managing increasing levels of need, meeting parental expectations. What I have discovered, however, is that some problems are so entrenched that many of my colleagues do not even notice them, even though they threaten the freedoms, rights and potentiality of young children, the way the profession is seen by others and the way we are regulated. Play is maligned or even deemed a waste of time, at times failing to engage children’s minds (Ofsted, 2024).

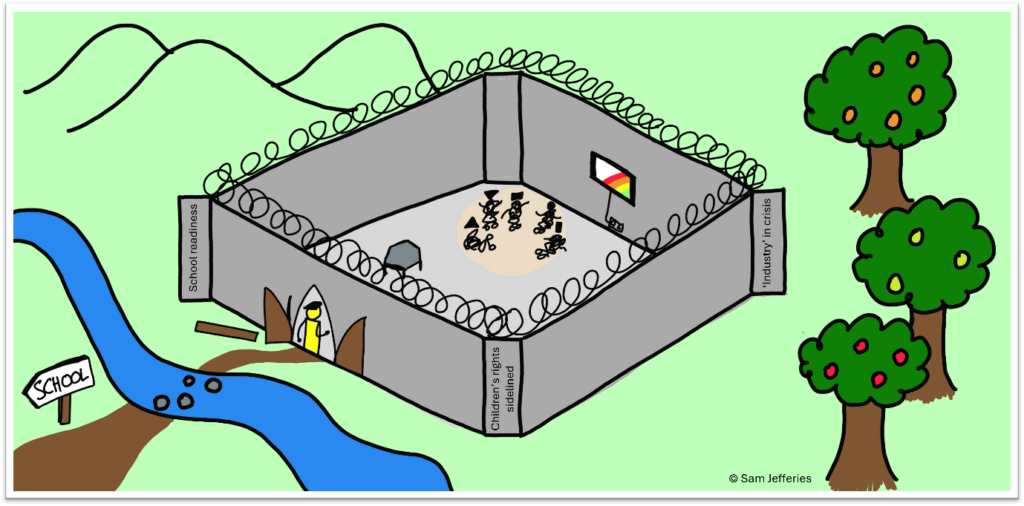

The walls surrounding us

The Early Years Foundation Stage statutory framework is a perplexing document full of contradictions: it declares that children are unique, play is important and settings are to craft their own curricula. On the other hand, the Early Learning Goals are seen as a gold standard, labelled as a ‘Good Level of Development’, describing where children ought to be and identifying where they are at risk of falling behind in order that they can transition well into Key Stage 1 and beyond (DfE, 2022: 5). This emphasis on the future renders education an impatient process (Biesta, 2013), where each stage is about preparing for the one which follows it (Robert-Holmes and Moss, 2021: 106). Thus the concept of ‘school readiness’ trickles down to ever younger ages, creating an Early Years context which assumes linear development, basic milestones and transmissive education (Wood, 2020). The curriculum therefore has little time for play – slow pedagogy (Clark, 2023), intrinsic joyful motivation and personal adventure. The skills so valued by our neoliberalist society are ironically squeezed out of children in our neoliberalist educational system.

The barbed wire

The walls are enforced by our regulator but these ‘fictional stories claim to be non-fictional statements, presenting themselves as natural, unquestionable and inevitable’ (Moss, 2018:5). Children’s rights to play, to be heard and to express themselves are sidelined for the sake of assessed and documented achievement. Within the walls, our fragmented industry is in crisis: staff recruitment and retention are a disaster; parents struggle to afford their nursery bills; small settings and childminders are unable to make ends meet; political parties use us as a bargaining chip to win votes.

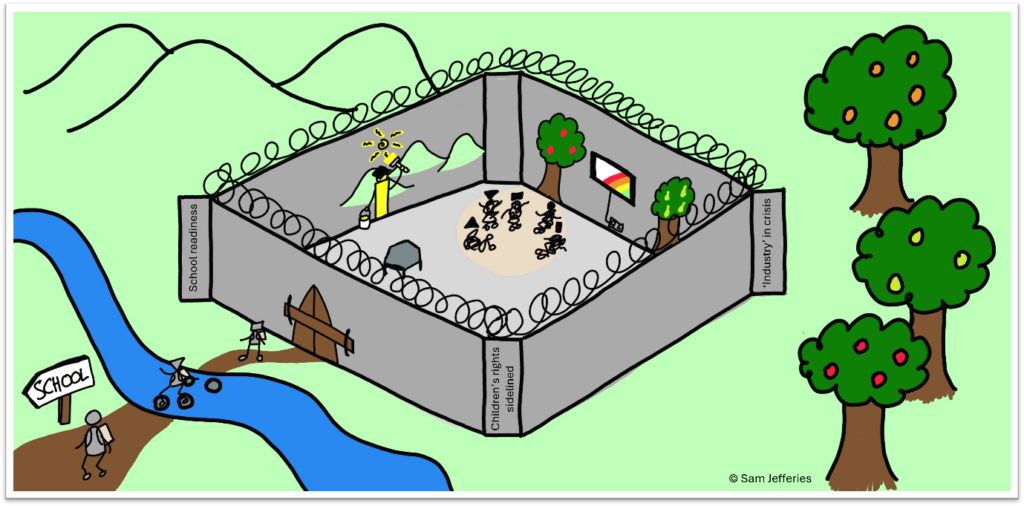

Painting the walls

As educators, we are increasingly shaped by the rhetoric surrounding teaching as an evidence-based profession (Slavin, 2002) where there is a perceived positivist model of best practice (Formosinho and Formosinho, 2016). Toolkits and programmes to improve our pedagogy abound, but when the ‘official’ story is so prevalent, data risks becoming one-dimensional as it is collected with a singular aim in mind (Clough, 2002). Pedagogy is thus reduced to the relationship between teacher behaviour and learner outcomes (Nind et al, 2016). However, if we only ever focus on pedagogy as craft, we are just painting the walls. Following the latest trends or purchasing the best marketed package without a critical lens does nothing to address the deep underlying issues and, importantly, children’s incredible potential is still limited by the neoliberalist constraints applied to them.

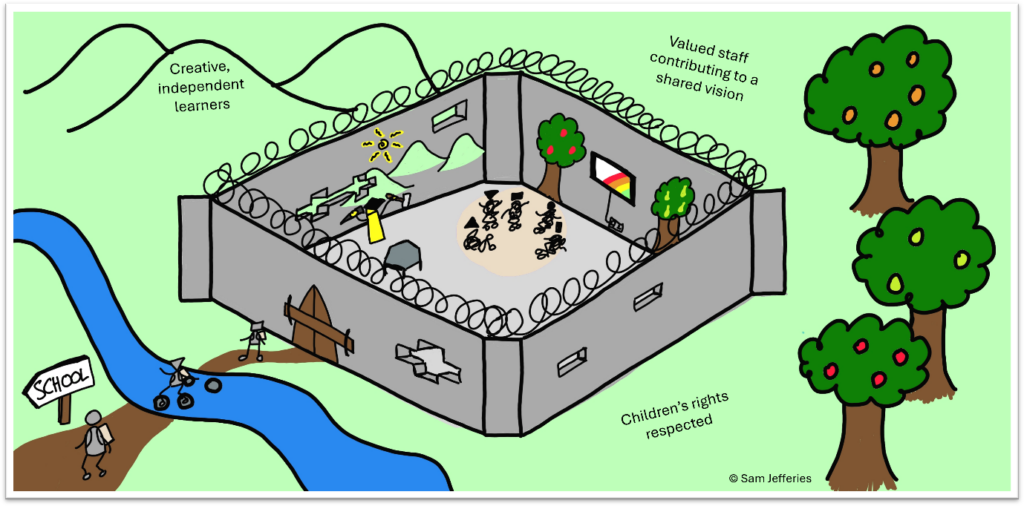

Making holes in the walls

If we are to move away from painting the walls then, how do we resist pervasive dominant discourses and make holes in them? It is fundamental to understand why we do what we do, remembering our pedagogical vision and considering how to navigate the system while clinging onto the values we know to be important (Fisher, 2024). This will look different for each educator, in our unique contexts with our unique children. We might consider, for instance, how to slow down (Clark, 2023), work with parents and communities (Rinaldi, 2021) or rethink the observations we make (e.g. Carr and Lee, 2012).

By challenging the three barriers of a school readiness agenda, the denial of children’s rights, and our demotivated and undervalued ‘industry’ (fragmented into private and state nurseries and preschools who must compete), I have sought to resist (Albin-Clark and Archer, 2023), striking a course for an alternative. This resistance is often subtle and under the radar, but it relies on research-informed practice as opposed to evidence-based practice; it may in fact pose problems rather than solve them (Biesta et al, 2019). It allows space to be reflexive about how we navigate the tensions and entanglements of our own unique contexts. Ultimately, it gives us hope for the future (Albin-Clark, Archer and Chesworth, 2024): that our children will be and become wayfarers into the unknown (Ingold, 2016), creative and flexible thinkers who can process and navigate risk (Anderson et al, 2014; Li, 2022).

If you too have resistance stories to share, please visit Resistance stories – Children’s right to play | Research projects where Dr Jo Albin-Clark and Dr Nathan Archer are recording stories about how we protect children’s right to play in order to share hope. There are, after all, other worlds outside the walls (Andrews, 2014: 360).

References

- ARCHER, N. and ALBIN-CLARK, J., 2023. Playing social justice: How do early childhood teachers enact the right to play through resistance and subversion?. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/4z4pa6un

- ALBIN-CLARK, J., ARCHER, N., & CHESWORTH, L., 2024. Storying hopeful resistances to datafication: Cracks, spacetimematterings and figurations of agency within the more-than-human ecologies of early childhood education and care. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 25(3), 347-364. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/14639491241267947

- ANDERSON, N., POTOČNIK, K. and ZHOU, J., 2014. Innovation and Creativity in Organizations. Journal of Management. 40 (5), pp. 1297-1333. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527128

- ANDREWS, M., 2014. Narrating Moments of Political Change. In: C. KINNVALL, H. DEKKER, T. CAPELOS and P. NESBITT-LARKING, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Global Political Psychology. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 353-368

- BIESTA, G. J. J., 2013. The beautiful risk of education. Boulder: Paradigm Publishing

- BIESTA, G., FILIPPAKOU, O., WAINWRIGHT, E. and ALDRIDGE, D., 2019. Why educational research should not just solve problems, but should cause them as well. British Educational Research Journal. 45 (1), pp. 1-4. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/berj.3509

- CARR, M. & LEE, W., 2012. Learning Stories: Constructing learner identities in early education. London: Sage Publications

- CLARK, A., 2023. Slow Knowledge and the Unhurried Child. 1st ed. Milton: Routledge.

- CLOUGH, P., 2002. Narratives and fictions in educational research. Buckingham: OUP

- DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION., 2023. Statutory framework for the early years foundation stage. London: Department of Education. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-foundation-stage-framework–2

- DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION., 2022. Early Years Foundation Stage profile: 2023 Handbook. London: Department of Education. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/46y2tuj4

- FISHER, J. (2024). Starting with the child? 5th ed. Maidenhead: OUP

- FORMOSINHO, J. and FORMOSINHO, J., 2016. Pedagogy-in-Participation. In: J. FORMOSINHO and C. PASCAL, eds. Assessment and Evaluation for Transformation in Early Childhood. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 26-55.

- INGOLD, T., 2016. Lines. Abingdon: Routledge

- LI, L., 2022. Reskilling and Upskilling the Future-ready Workforce for Industry 4.0 and Beyond. Information Systems Frontiers, pp. 1-16. Availble from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35855776

- OFSTED, 2024. Strong foundations in the first years of school.

- MOSS, P., 2018. Alternative Narratives in Early Childhood. 1st ed. United Kingdom: Routledge.

- NIND, M., CURTIN, A. and HALL, K., 2016. Research Methods for Pedagogy. 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing

- RINALDI, C., 2021. In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia. 2nd ed. United Kingdom: Routledge.

- ROBERTS-HOLMES, G. and MOSS, P., 2021. Neoliberalism and Early Childhood Education: Markets, imaginaries and governance. London: Routledge.

- Slavin, R. E., 2002. Evidence-Based Education Policies: Transforming Educational Practice and Research. Educational Researcher, 31(7), 15-21. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X031007015

- WOOD, E., 2020. Learning, development and the early childhood curriculum: A critical discourse analysis of the Early Years Foundation Stage in England. Journal of Early Childhood Research : ECR. 18 (3), pp. 321-336. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1476718X20927726

Victoria Jefferies is studying for her MA in Early Years Education at Edge Hill. Her main interests are the pedagogy of adventure and practitioner voice. She has previously worked in Lancaster EY settings, leading on curriculum and pedagogy.