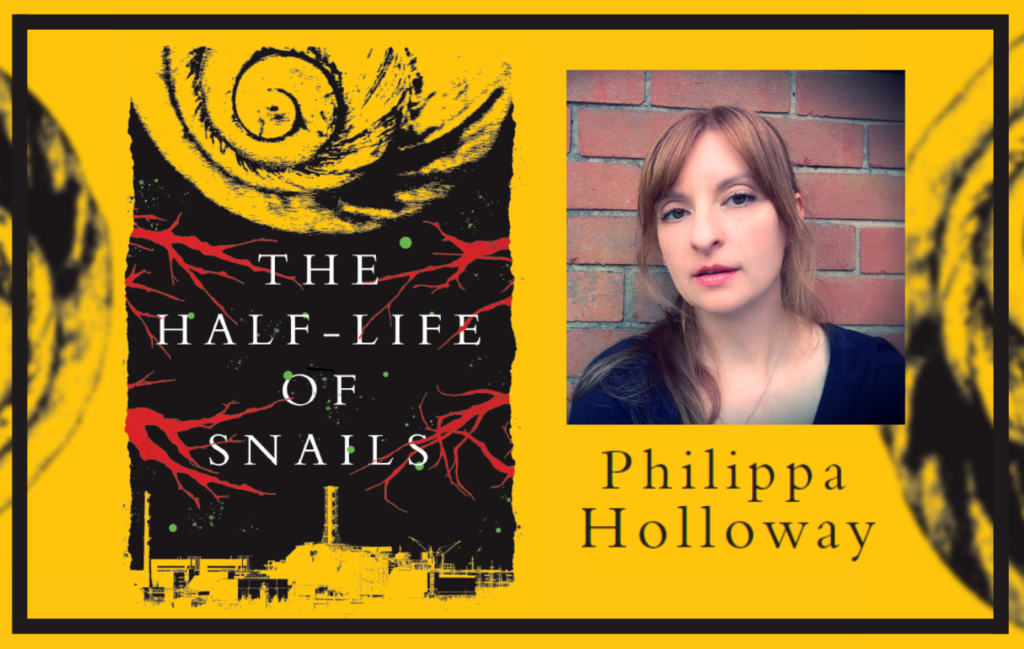

Dr Philippa Holloway

Creative Writing often embraces other disciplines. While academic research within this field focuses on research in Creative Writing (the theories and practices of creative expression), essentially writers must also research for their writing. They must learn about and consider psychology, geography, science, history, sociology, geology, ethnography, and philosophy as well as develop methodologies from other practitioners and arts. Creative Writing brings these disciplines together through narratives that question and explain.

I am, as a writer, curious and determined. I knew that if I wanted to write about nuclear anxiety, about complex responses, I needed to face my fears head-on. I booked a trip to Ukraine shortly after the Euro Maidan Revolution and headed alone to Chernobyl’s Exclusion Zone to engage with the landscape and people.

While limited to a few days, it allowed me to experience the irradiated and varied landscapes, to hear first-hand of the legacy of nuclear accident, to capture the feel of the place. Most importantly, I was able to talk to some Samosely, the self-settlers who returned to their homes after evacuation, refusing to leave again, because their connection to home was stronger than their fears of radiation.

These themes – accident, human error, anxiety, hope, homesickness and determination to protect territory and self – are entangled and often intangible, and form the core of my novel. Yet it isn’t a story about me. Fiction is a medium that both condenses and expands simultaneously. Characters and situations can be stretched, pushed imaginatively to extremes, or beyond realism into speculation as a means of discovering clarity on certain issues. Much is discovered by asking ‘what if?’ over and over. Ideas, issues, themes and concerns are then compressed into a manageable, accessible and dynamic form, a narrative that engages the reader in the depths and nuances of the topic.

As a brief example of this expansion and compression from my own novel, I will focus here on the title of the book. It is a title that plays with the issues at hand: Half-lives are both a scientific concept, measuring radioactive decay, and a metaphor for times passing, things deteriorating, and change. Snails carry their bunkers on their backs, are able to shelter until danger passes. In the novel, these two ideas come together in the child’s interactions with his pet snails, which are marked out in the narrative as changing over time and responding to the deterioration of the situation around him. It’s representative. Distilled and yet stretched to encompass multiple interpretations.

Considering the complex nature and conflicting emotions ignited by nuclear power, especially now as the pressure to replace gas and oil becomes critical, storytelling is perhaps an ever more vital means of engaging with these issues. Fiction allows room for questions to be asked and answered by both writer and reader, and while the words may be fixed on the page, each reading ignites new responses and engagements. This novel is therefore not the culmination of an investigation of anxiety, but part of a wider debate and collective exploration of the issues, a collaborative interrogation of our relationship with nuclear energy that will not end anytime soon, considering the half-life of the materials in question…

Dr Philippa Holloway is a writer and academic, teaching Creative Writing at Staffordshire University and former Graduate Teaching Assistant at Edge Hill University. Her debut novel, The Half-life of Snails, is out now with Parthian Books.