‘’I didn’t have time to play today. I wrote my name, I did some sums, I read my book to the teacher and wrote some sentences with full stops and speech marks. I painted a self-portrait and did lots of other things, but I didn’t have time to play today, or yesterday. Hopefully I will play tomorrow?”

The child’s voice

Assessment in Early Years Education has received considerable attention in recent years. Children in England today are officially assessed five times by the end of their Primary School years (DfE, 2014. Reforming Assessment and accountability for Primary Schools). The information obtained from these assessments is translated into numerical figures and it seems as if the impact of play is lost amongst this culture of labelling. Although many have written about the consequences of some assessment procedures (Bradbury & Roberts-Holmes, 2017; Dubiel, 2016), what current discussions highlight is not a pledge towards the avolition of assessment in early years. The discussion is bringing to the surface the need for clarification and the actual use of assessment in Early Years Education and Care (ECEC).

Open the doors to play

We seem to have developed a ‘scary’ perception of assessment that has formality attached to it and sets out lists of goals to work towards when all that is necessary is to simply let play back in.

The themes drawn from the discussions I have had with practitioners from different backgrounds recently highlighted the absence of spontaneous play during crucial times. I found myself referring to the journals I had written years ago which told stories about the children I worked with. Those accounts of children’s progress ALL had a common thread which I had not identified at the time and this made me realise that we had allowed concepts in that had manipulated the value of play.

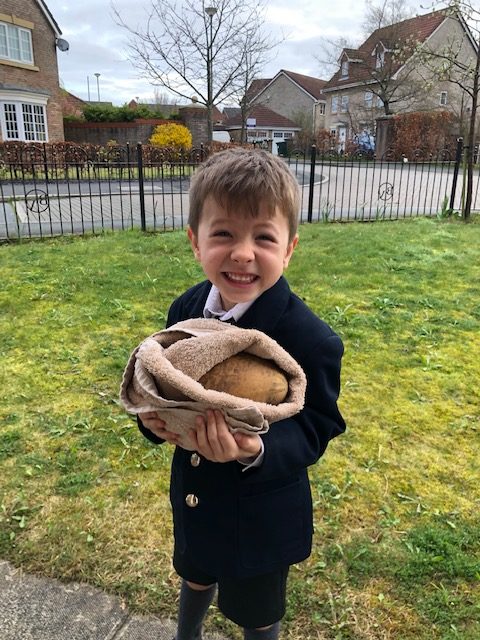

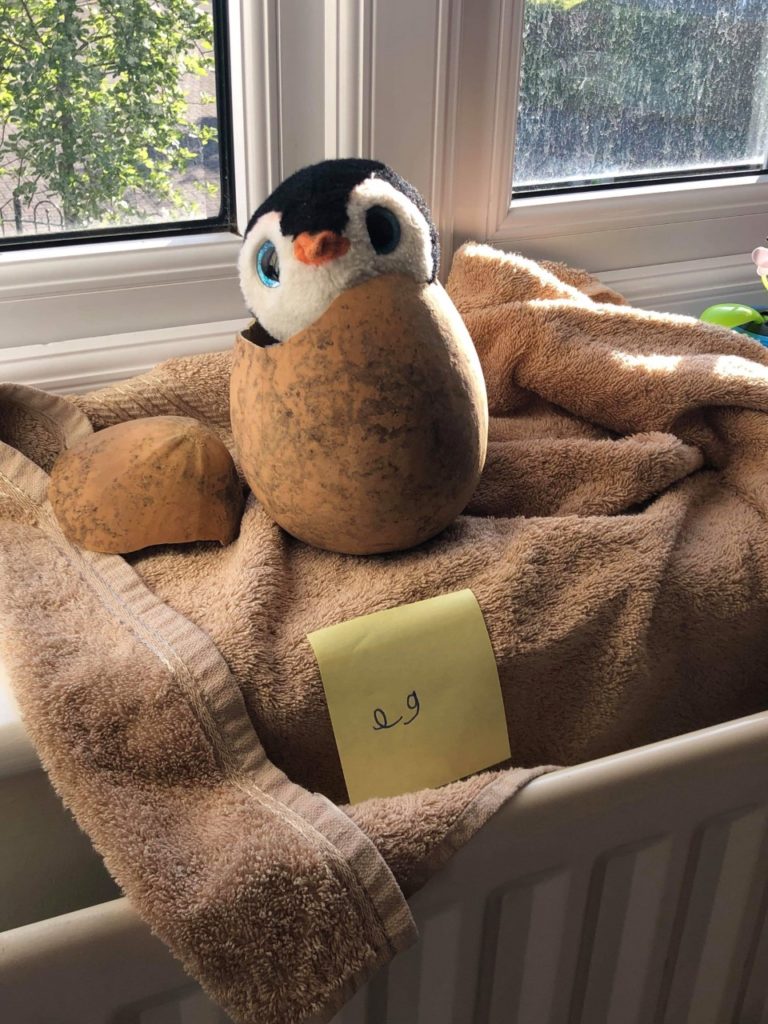

‘A dinosaur adventure’ that became real because Alex reminded us that spontaneous play has an impact that cannot be predicted. These photographs show us how Alex took charge of his play and let assessment and play walk alongside each other when he said, “dinosaurs are real”.

The formalised approach to assessment we have been forced to follow would encourage us to relate each part of the experience to the EYFS Framework or any other policy document that is used as a guide for assessment purposes. However, what happened to Alex when he brought play to life, had an impact that cannot be numerically measured. The introduction of scores to measure how children are progressing has influenced practitioners to justify the use of play. Alex’s adventure is evidence of the type of play that has no prescribed agenda. These types of experiences reiterate the importance of allowing spontaneous play count.

The current culture of progress justification has had an impact on how play is perceived by some practitioners and this is how pockets of ‘play depravation‘ have been identified. This is not necessarily because children have been deprived of play, rather because spontaneous play is often not understood and therefore manipulated to fit into the progress ranking agenda.

Play in its natural sense has never gone away, it has been hidden under a numerically measurable agenda. Turning that on its head is the starting point. Do we need numerical scores to justify that children are learning and developing (Gullo, 2005)? Assessment can be carried out whilst children have the freedom to explore the world through play. It is in fact recommended by many that we start learning about each child before we measure where they fit within these ‘ready-made progress scales’. Assessment does have a place in Early Years but, it needs to value strategies that help us as practitioners understand how children are developing. How about we assess children during play to really learn about who they are? Play can allow us to enter a child’s world where assessment can happen authentically. As we let children discover the world, we can witness how they flourish as unique individuals. This happens when children simply play (Nilsson et al, 2018; Martin, 2018).

Observing Alex play with ‘the dinosaur eggs’ he found in his allotment (which were dried out squashes) helped us learn about him. I know more about Alex because I was able to see him totally immersed in his play.

Whilst I write about the power of play

Alicia Blanco-Bayo

I do wonder what children might say

“Watch me, hear me! Let me be!”

It is through play that you’ll learn about me!”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BRADBURY, A & ROBERTS-HOLMES, G. (2017) Creating an Ofsted story: the role of early years assessment data in schools’ narratives of progress. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(7), 943-955.

DfE (2014) Reforming Assessment and accountability for Primary Schools. London: DfE

DUBIEL, J. (2016) Effective Assessment in the Early Years Foundation Stage. SAGE: London

GULLO, D. (2005) Understanding Assessment and Evaluation in Early Childhood Education. 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

MARTIN, S. (2018) Take a Look. Observation and Portfolio Assessment in Early Childhood (Seventh Edition) Canada: Pearson.

NILSSON, M., FERHOLT, B. & LECUSA, R. (2018) “‘The playing-exploring child’:Reconceptualizing the relationship between play and learning in early childhood education”, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, vol. 19, no. 3,231-245.

OFSTED (2017) Bold Beginnings: A Reception curriculum in a sample of good and outstanding primary schools.

For further reading please visit:

https://www.interactionimagination.com/blog

https://www.earlyyearsstaffroom.com/blog/

https://www.keyu.co.uk/keyu-blog/

2 responses to “‘Assessment overload’ – play depravation?”

This is such an important and timely theme, which brings new dimensions to the early years practice. In my opinion, despite the ongoing debates related to the assessment overload, few researchers, actually, suggest any specific ways, in which early years pedagogy can be re-conceptualised and reflected in the EYFS in a practical way. These examples are fantastic in terms of contributing to these developments!

A very refreshing & ‘real’ account- Alicia has shown how a simple method can better facilitate understanding & expressions of genuine development in children.

Didn’t the children of previous decades learn so much sooner by being hands on in a natural environment & were as keen to learn at school with teachers who were not stressed about assessment deadlines?