Matthew Greenhalgh

Quality education, often measured through an individual’s academic achievement, is a proven factor of later successes in academia and employment, and has the potential to improve health outcomes, increase income, and support social mobility. However, research suggests disparities are presented across socio-economic classes, with disadvantaged students’ experiences of education and opportunities for learning or development disproportionally affected. The impact of COVID-19 has exacerbated the problem for these students who have reportedly been most affected by school closures throughout the pandemic. With simple ‘attempts to raise achievement among disadvantaged children’ failing, such as additional funding for students from less advantaged backgrounds through the Pupil Premium grant, introduced in 2011, it is vital that decision makers and practitioners are aware of how to best support their ‘catch-up,’ while understanding impediments to progress.

As such, we need a broader understanding of the richer relationship between disadvantaged students and their achievement. Though the poor performance of less advantaged students is widely acknowledged and occasionally accepted, recognising that despite the posited correlation, an individual’s socio-economic status does not determine or predict their achievement. Instead, it influences their achievement indirectly, through various factors of broader development. Such factors could be conceptualised as ‘mechanisms’. ‘Mechanisms’ have a potential effect upon the outcome of an individual’s achievement, and the varying dependent which socioeconomic conditions present. Examples of these factors include diet and exercise, with both shown to be important for learning, essential to brain development and functioning – but strongly influenced by socio-economic status. Additionally, assessment of such achievement may be posited as another mechanism, with further concern that an individual may not ‘achieve’ their academic potential or present their actual academic ability due to how they engage with the assessment. Here they are hindered by communication, bad exam technique or due to the fallibility of assessments for measurement of their achievement.

Beyond recognising some of these additional factors which are influential to the richer relationship, and conceptualising how they may be influential, it can be helpful to consider how such relationships may be represented visually – so the network of interactions may be observed and traversed.

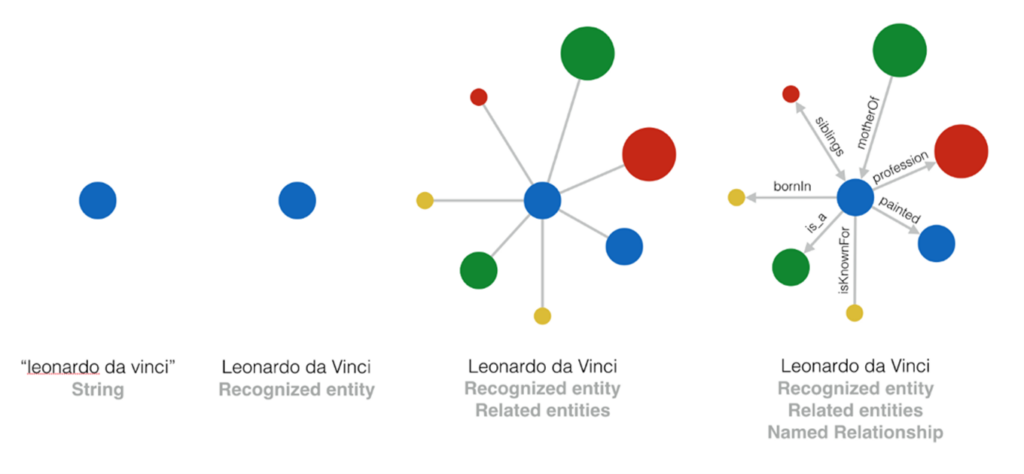

‘Knowledge Graphs’ offer a means of visually mapping these relationships. , Introduced by Google in 2012, these graphs describe their efforts to improve search results by connecting information and relationships in a structured way. Knowledge graphs present a framework for representing connections between entities, concepts, or mechanisms (as nodes) through the relationships between them (as edges). In the context of disadvantaged students, this would highlight the relationships between factors such diet, exercise and means of assessment, allowing us to better understand how these factors collectively influence students’ achievement. Both nodes and edges may also have additional properties (labels, attributes, descriptions, etc.) which provide further detail and context, such as variation dependent upon socio-economic status. The simple diagrams below from Google demonstrate evolution of a knowledge graph, from an arbitrary ‘string’ to a more recognisable entity and its relations.

This blog follows a presentation at ACRE23, held at Edge Hill University, which explored how such a relationship may be conceptualised and represented more broadly. It aims to establish a premise under which future empirical research may take place and presents a rigorous approach for understanding the richer relationship between disadvantaged students and their achievement, through academic research which is much more socially responsible.