Bob Nicholson, Edge Hill University

Laughter: it’s said to be the best medicine and the cheapest form of therapy. Studies have shown it can help to boost immunity, relieve tension and even reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression – it seems there’s a lot to be said for having a good old laugh.

The idea of laughter being good for our health has deep roots. It was certainly in wide circulation during the Victorian era, meaning that despite popular stereotypes of this straitlaced century – in which the people and their Queen were terminally “not amused” – laughter was thought of as an essential component of good mental and physical health.

The introduction to the Railway Book of Fun (because who doesn’t need more fun on a train), which was published in 1875, proclaimed that cheerfulness was a “christian duty” and advised readers to “use all proper means to maintain mental hilarity” if they valued “health and comfort”. It even argued – rather optimistically – that a good sense of humour could help ward off infectious diseases.

Not all Victorians were so keen to loosen their stiff upper lips though. In 1875, a man named George Vasey declared war on laughter. In his book The Philosophy Of Laughter And Smiling he argued that only “the depraved, the dissipated, and the criminal” were “addicted to uproarious mirth.”

Over the course of 166 pages, he attempted to scientifically prove that laughing was an idiotic, vulgar, and ugly habit enjoyed by empty-headed fools. Laughter distorted the face and, Vasey warned, “often ended fatally” by blocking the passage of air to the lungs. Sensible people, he concluded, “never laugh under any possible circumstances”.

Laugh and grow fat

Vasey certainly wasn’t the only Victorian to argue for a new culture of seriousness, but the truth is that these anti-mirth campaigners were swimming against the tide. As Vasey himself admitted, the “immense majority” of his contemporaries held “the habit of laughing in high estimation” and regarded it as “an absolute necessary of life”.

The proverb “laugh and grow fat” circulated widely in the 18th and 19th centuries and was usually intended as a recommendation. This link between fatness and health might seem odd to us today. But as one 19th century journalist explained:

[This was not to suggest] that a mere state of obesity was especially desirable, but rather a wish to rebuke the evil effects upon the physical systems engendered in the persons of those whose lives are made up of fretfulness, of melancholy, and of sour-faced bigotry.

For advocates of this philosophy, a good sense of humour could even lead to a slap-up meal. Jokes were an important part of Victorian “table-talk” and accomplished raconteurs were sought-after guests at dinner parties. One Victorian writer explained how a skilled and original humorist could “extract venison out of jests, and champagne out of puns”.

For less accomplished comedians, scores of joke books and ready-made “manuals of table-talk” were on sale at Victorian bookstalls.

Fond of fun

Just like today, the possession of a good sense of humour was considered an attractive quality by Victorian men and women when seeking a romantic partner. Back then, “matrimonial advertisements” – the equivalent of a modern day Tinder profile – routinely described their authors as “jolly” and “fond of fun”.

Some Victorian men even pretended to have written jokes for Punch magazine in the hope of “ingratiating [themselves] with the fair and trusting sex”.

A small community of Victorian humorists also managed to earn a living by writing jokes. As one of these professional gag writers put it, he spent his day “turning out jokes as other men would turn out chair-legs”.

The most prolific jesters in the UK and US were reportedly capable of writing 100 new jokes in a day before selling them to the editors of comic magazines like Punch and Fun. These papers circulated widely, and as Vasey begrudgingly explained:

[The publications] realised princely incomes by their successful efforts in stimulating the pectoral muscles and shaking the diaphragms of their numerous readers.

Private jokes

While most Victorian joke books limited themselves to respectable humour, racier jokes were, it seems, told in private. The story goes that at one of Punch magazine’s legendary weekly dinner gatherings, political debate about the merits of the then prime minister’s reform bill was abruptly redirected when the journalist Shirley Brooks interjected with a joke:

Q. If you put your head between your legs, what planet do you see?

A. Uranus

The British novelist William Thackeray was reportedly consumed with laughter and then proceeded to crack a joke about his own problems with urethral stricture – so much for the link between laughter and good health.

In short, most Victorians loved to laugh. Despite the best efforts of George Vasey and other champions of seriousness, a vibrant culture of comedy existed in 19th century Britain. And yet, much of this humour has never been studied by historians. Which is why, for the last few years, I’ve been working on a project with the British Library that aims to celebrate this under-appreciated aspect of Victorian life.

We are building an online archive of long-forgotten 19th century jokes. It’s still under construction, but we’ve already begun sharing some of the “best” gags on Twitter and Facebook.

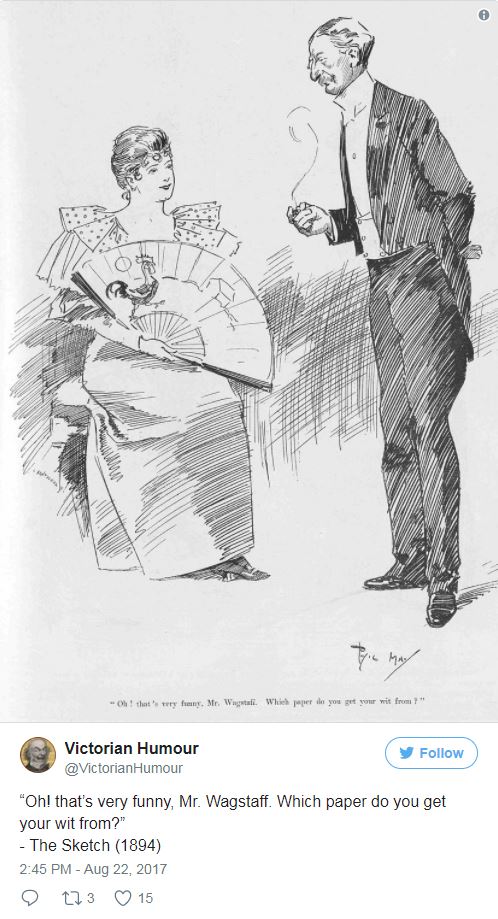

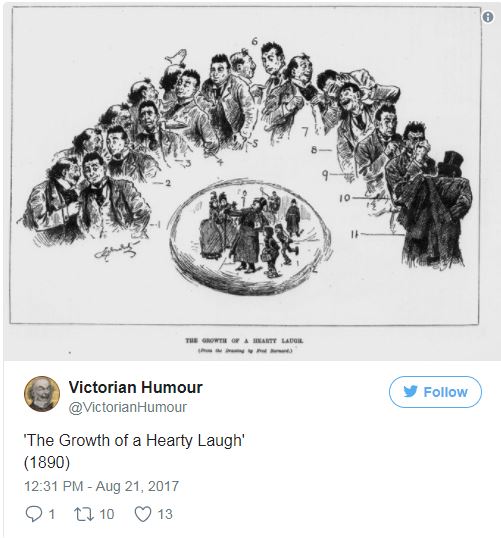

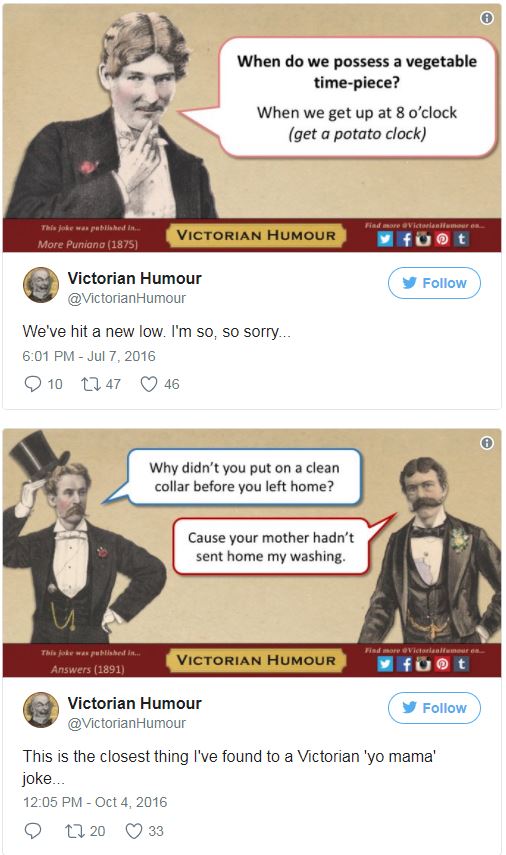

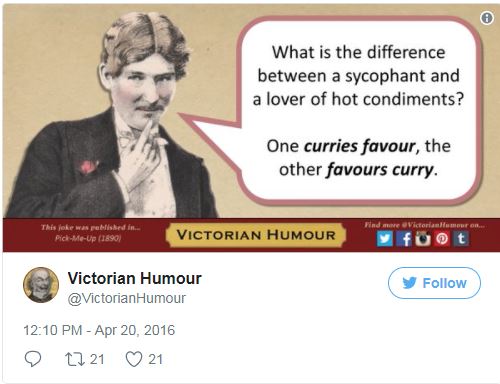

Here are some of my favourites:

![]() Perhaps George Vasey had a point after all.

Perhaps George Vasey had a point after all.

Bob Nicholson, Senior Lecturer in History, Edge Hill University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.