As long as we have not destroyed everything, there will remain ruins.

– Student slogan from May ‘68

Last week, as part of this semester’s ‘make it new’ theme, I introduced the Reading Group to the work of photographer Camilo Jose Vergara, and in particular, his website Invincible Cities: http://invinciblecities.camden.rutgers.edu/intro.htm

This website is unlike anything I’ve seen before; a dense, multi-layered, visual history of American ghettos in the South Bronx, Harlem, Detroit and other places. I think it harnesses the possibilities of web 2.0 in new and interesting ways, and, more importantly, couldn’t be published as a book. If you visit the website you’ll see what I mean – a warning; make sure you have a speedy connection because it needs fast download speeds to enjoy it properly.

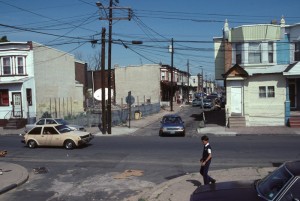

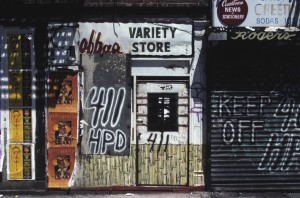

Camilo Vergara, originally from Chile, is a sociologist (although this notion came under rapid assault from some members of the group) and a photographer (this did not). I introduced his work to the group for two main reasons; first, I really like his photographs. Here’s some to give you a flavour:

Second, I like the way his uses photography as a form of visual research. This is Vergara on his working method: “I use photographs as a means of discovery, as a tool with which to clarify visions and construct knowledge about a particular place, or city.” His photography, then, is a way of mapping the urban landscape and the slow changes that happen to it over an extended period of time; you get a real sense of this if you explore the website. As someone who teaches in the Media Department, I’m particularly interested in ways of using practice (making films, taking photographs) as research; so my key question to the group was this: how can photography create knowledge?

The responses were mixed and vigourous; some challenged Vergara’s status as a sociologist immediately, questioning his working ‘methodology’. We had a long debate about the merits of ‘quantitative methodology’ in the social sciences and how such terms could be applied to Vergara, if at all. As you can see from these examples, Vergara’s work deals with extreme poverty and racial segregation.

His work provoked a lively discussion about urbanism, race, and representation. What does it mean to enter into these types of communities and photograph as an ‘outsider’, as someone merely passing through? There was much criticism of the work for this reason. We talked through some of the issues and wondered how the images produced would be different if the people who live in these blighted communities were given camera themselves.

Does taking a photograph change anything? What can it tell us? Jean Luc Godard’s punning response to a photograph of Jane Fonda in Vietnam during the war in South-East Asia is telling here: ‘This is not a just image,’ he says, ‘it’s just an image.’ Susan Sontag’s work, too, was also invoked as we discussed notions of detachment, proximity and closeness in photography generally, and with regard to Vergara’s work in particular.

The most telling response from most people – and one in my academic eagerness I had overlooked – was aesthetic; these photographs, with the casual look of rough and ready snapshots, are beautiful objects. (A few people fancied them as prints for their living room). In framing the ruins of modern America, Vergara’s photographic eye offers up a vision of the United States as an iconic surface; the run-down houses, the empty streets, the burnt-out Cadillac’s – all unmistakable images of America, rendered as a distant, foreign land.

It was also commented that, in some sense, Vergara’s work was more poetic than sociological (do the two categories have to be distinct, I wonder? Can there be such a thing as ‘poetic sociology’?) In looking at Vergara, we discussed Roland Barthes distinction in his beautiful meditation on photography, Camera Lucida, between studium and punctum; and we wondered at how photographs evoke a certain phenomenological ‘thereness’ in the image; this person, that object, were actually there in front of the camera. In the case of Vergara, this again stirred up discussions about the ethics of detachment when framing the world through a camera lens.

We covered a lot in an hour and we also had lovely sandwiches and cake. Come along and join us next time.

– David Jackson, Lecturer Film & TV

One response to “Academic Reading Group: Camilo Jose Vergara”

Woodlands has many advantages – proximity to a range of exciting and interesting discussions like this is not one of them…so please bear with my attempts join in the conversation from a distance, not having had the benefit of its tone as well as its content.

I do wish I’d been able to be at this session. As someone interested in methodology, and alternative methodological perspectives, I’m really interested in methods of capturing the “thereness”. When I was a master’s student on an action research degree, my supervisor used to say to me “just tell it like it is”. Perhaps Vergera has found a way to “show it like it is”? The issue of doing so as an outsider or insider is something that is always present in social science research. My own perspective on this is that it is never actually possible to do ANY research completely as an outsider, or at least in an ‘objectove’ way – but that’s a whole nother story…

As for poetics vs sociology, I guess my take on that is one that relates to both the art and the science of fractals. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Julian_fractal.jpg for example. This is just one very small example of the myriad ways in which science has an inherent art, and indeed a poetry, music and spirituality. To separate science from these constituents, and indeed to do so in an oppositional way, suggests to me an incomplete understanding of each.

While I find typologies and classification systems helpful at times, I am always conscious of their potential for limiting thinking.